Thank you to The Socialist Unity Blog for this idea. This thread is open to whatever you want to discuss; politics, art, blogging, etc. This is the thread, to say the things, that don't fit other threads.

See the John Brown parody site, Thavage Juthice, which parodies Savage Justice. The blog was created by John's rightist admirers. John has been a great contributor to the comments on this blog, getting heat left and right. I'm too boring to be parodied.

I'm reading Deutscher's biography of Trotsky. I'm having to arm myself, to debate my Maoist friends.

I'm involved with the Minnesota Fringe Theater Festival, producing a show featuring Sentir Venezolano, a Venezuelan folkloric dance company, featuring dance, percussion, and vocal music. I'm also helping to promote The Minnesota Heartland Tango Festival.

I'm amazed how I find about weekly people who link to this blog, from blogs I have never visited. See: Who Links To Me. I don't think that agreement should be the only basis to trade links. I link on the basis of entertainment value, smartness, and visiting my blog. I also link to blogs that I plagiarise.

I believe Sonia is authentically a nudist from Tonga. That is more of a controversy on her own blog.RENEGADE EYE

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Cuba: Revolution Revisited.

I'm reprinting an overview article, summarizing a six part review of Samuel Farber's "The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered" (University of North Carolina Press,2006), reprinted from Paul Hampton's Blog at Workers\' Liberty. I found this entry challenging and provocative.

Although critical of Fidelistas, it is not a call to support the blockade, or the reactionary opposition to Castro.

The Cuban revolution revisited: Part I – Overview

What was the class character of the Cuban revolution of 1959-61? More than any other Marxist over the last forty-five years, Sam Farber has tried to tackle this question from the standpoint of Third Camp working class socialism.

Farber was born and grew up in Cuba. Since the early 1960s he has been an active revolutionary socialist, most recently as a member of the Solidarity organisation in the United States that publishes Against the Current magazine.

His earlier book, Revolution and Reaction in Cuba 1933-1960 (Wesleyan University Press, 1976) is the most coherent Marxist explanation of the Cuban revolution to date. Now this new book, The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered (University of North Carolina Press, 2006) updates his interpretation in the light of scholarship published over the last thirty years.

Farber uses original documents, biographies and other sources emanating from Cuba and elsewhere, fleshing out some issues that were previously not well known or understood. In particular he uses declassified US State Department files and Soviet documents to clarify a number of crucial matters.

What happened in the Cuban revolution?

There is little dispute about the broad outlines of the Cuban revolution 1959-61.

Before the revolution, Cuba was ruled by a military dictator Fulgencio Batista, who seized power in a coup in 1952. A range of organisations - and even sections of the military - challenged Batista’s rule, including the group around Fidel Castro, which attacked the Moncada barracks on 26 July 1953. Although the attack failed and the participants imprisoned, they were released and exiled two years later.

Castro’s group, now known as the July 26 Movement (M26J), returned to Cuba in December 1956, launching a guerrilla struggle against Batista from the mountains of the Sierra Maestra. Other urban groups, such as the Directorio Revolucionario and the Partido Socialista Popular (PSP, the Cuban Communist Party) also opposed Batista. In April 1958 the M26J called a general strike, but it largely failed.

However Batista’s offensive against the guerrillas in July 1958 failed and by the end of the year his forces had been driven back. On 1 January 1959 Batista fled and his army collapsed. The M26J took over, celebrated by a general strike lasting four days.

Castro’s political revolution was consolidated when leading Batista figures were tried and executed and the new regime passed a series of reforms, notably an Agrarian Reform Law in May 1959. Castro himself became prime minister in February 1959. In November 1959 pro-Castro and Communist (PSP) supporters took control of the trade union movement.

Towards the end of 1959, the US government began making plans to overthrow the Cuban government – and Castro began making links with the USSR. In May 1960 the government took complete control of the media. In the following months US oil and other businesses were expropriated. In April 1961 the US sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion failed and Castro declared the “socialist” character of the Cuban Revolution – in reality a social revolution that created the first Stalinist bureaucratic social formation in Latin America.

Why was there a revolution in Cuba 1959-61?

Lenin argued that revolutions come about when the ruling class is no longer able to rule in the old way, and the mass of people are no longer willing to be ruled in the old way.

This means trying to understand the circumstances that made a revolution possible – but also clearly identifying the agents involved, their aims and strategies for power.

Any explanation of the nature of the Cuban revolution has to grapple with five key issues:

1) The political economy of Cuba before and after 1959;

2) The nature of the Castro group that led the revolution, and other parties contending for power (e.g. the PSP);

3) The role of the US government in pushing Castro towards Stalinism;

4) The role of the USSR and the PSP in attracting the Cuban regime towards its orbit; and

5) The role of the working class and other classes in the process.

Most “left-wing” explanations of the Cuban revolution address these issues in the following way:

1) They emphasise the backward, dependent nature of Cuban capitalism, dominated by imperialism and ruled by a dictatorship often depicted as a puppet of the US.

2) They depict the Castro group as radical nationalists, but pragmatic revolutionaries who evolved their programme and strategy as they went along.

3) They emphasise the US government’s imperial bungling, which pushed the new regime away from bourgeois-democratic rule towards “socialism”.

4) The role of the USSR is presented as benign or even progressive, coming to the aid of the Cuban government when it came under attack from the US.

5) The working class is presented as an integral part of a popular, multi-class alliance that eventually put its representatives (the Castroites, sometimes with the PSP) in control.

In most “Trotskyist” accounts, this is sometimes dressed up as “permanent revolution”, whereby a process of growing over from a national-democratic revolution to a socialist revolution is asserted, with Castro’s leadership playing the locum role for a Marxist party. Differences about the nature of Stalinist rule in Cuba revolve around the extent of bureaucratic “deformation” or “health” of a “workers’ state”.

The central problem with this approach is that it displaces the working class from the centre of the analysis, substituting the Castro group as the progressive agency. The working class is at best perceived as a subordinate prop for the Castro regime – rather than the victim of its rule. Despite the absence of mass workers’ organisations, such as soviets (factory councils) or factory committees, and the absence of a Marxist party leading a class conscious working class to take power in its own interests, proponents of this view describe with ever great detachment from reality the manner in which the Cuban working class “rules” vicariously through the agency of Castro’s state. They forget that a “workers’ state” created without the active intervention of the working class is no workers’ state at all.

There are also right-wing explanations of Castro’s rise to power.

1) These emphasise the developed nature of Cuban capitalism in the 1950s and suggest that Batista would have given way to some form of bourgeois democracy.

2) They depict the Castro regime as Stalinist from the start, as a conspiracy that carefully concealed its true nature within a broadly democratic movement before foisting its real designs on the Cuban people after two years in power.

3) The US government is usually presented as moderate, protecting the interests of its businesses, sometimes making mistakes – but essentially benign;

4) By contrast, the USSR is portrayed as pulling Cuba towards its orbit from the beginning.

5) The working class is presented as duped by Castro’s promises – or is simply irrelevant to government-level machinations.

The main problem with this view is that it completely misunderstands the international context in which the Cuban revolution took place and the various contending forces that vied for power. It too fails to grasp the reality of the situation for Cuban workers before and after 1959, so provides no conception of what workers could have done in the situation – or what lessons can be learned for today.

Neither of these broad views offers a class analysis of the Cuban revolution. Neither grasps the dynamics of the period, the motives of the key social agents nor understands the trajectory the regime took between 1959 and 1961.

By contrast, Farber’s view is much more nuanced. To summarise it tersely:

1) The political economy of Cuban capitalism in the 1950s was defined by uneven development and Batista’s regime is understood as a Bonapartist formation, balancing between social classes with little social base.

2) Castro’s group was a declassed populist movement in the tradition of Latin American caudillismo, an active agent with its own aims and with internal tensions and pressures – and faced competitors for power. It created its own form of Bonapartist rule before choosing the Stalinist camp.

3) US policy emanated from its imperial role in the hemisphere and its priorities in the Cold War - consistent with its treatment of other regimes in Latin America.

4) The USSR pursued its own imperial state interests and was involved from the early days in the regime – acting as a pole of attraction and actively promoted as a model by the PSP.

5) The Cuban working class lacked the kind of independent politics necessary to fight for its own interests and self-rule. Workers were not the social force that made the revolution, nor its ultimate beneficiary – indeed the working class was hegemonised and effectively exploited by the new class that came to rule by 1961, under what Farber has called a “bureaucratic collectivist class society”. (1976 p.237)

To sum up, Farber’s book is exceptionally useful, dispelling the veil of romanticism that surrounds Castro’s Cuba on the left. It is vital contribution towards reorienting the left and a tremendous contribution towards understanding the nature of the Cuban regime today. With Fidel Castro’s death likely to set off a chain reaction inside and outside Cuba, Marxists have a substantial task in seeking to understand the Cuban social formation and its direction. This book helps us to do that work.Renegade Eye

Although critical of Fidelistas, it is not a call to support the blockade, or the reactionary opposition to Castro.

The Cuban revolution revisited: Part I – Overview

What was the class character of the Cuban revolution of 1959-61? More than any other Marxist over the last forty-five years, Sam Farber has tried to tackle this question from the standpoint of Third Camp working class socialism.

Farber was born and grew up in Cuba. Since the early 1960s he has been an active revolutionary socialist, most recently as a member of the Solidarity organisation in the United States that publishes Against the Current magazine.

His earlier book, Revolution and Reaction in Cuba 1933-1960 (Wesleyan University Press, 1976) is the most coherent Marxist explanation of the Cuban revolution to date. Now this new book, The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered (University of North Carolina Press, 2006) updates his interpretation in the light of scholarship published over the last thirty years.

Farber uses original documents, biographies and other sources emanating from Cuba and elsewhere, fleshing out some issues that were previously not well known or understood. In particular he uses declassified US State Department files and Soviet documents to clarify a number of crucial matters.

What happened in the Cuban revolution?

There is little dispute about the broad outlines of the Cuban revolution 1959-61.

Before the revolution, Cuba was ruled by a military dictator Fulgencio Batista, who seized power in a coup in 1952. A range of organisations - and even sections of the military - challenged Batista’s rule, including the group around Fidel Castro, which attacked the Moncada barracks on 26 July 1953. Although the attack failed and the participants imprisoned, they were released and exiled two years later.

Castro’s group, now known as the July 26 Movement (M26J), returned to Cuba in December 1956, launching a guerrilla struggle against Batista from the mountains of the Sierra Maestra. Other urban groups, such as the Directorio Revolucionario and the Partido Socialista Popular (PSP, the Cuban Communist Party) also opposed Batista. In April 1958 the M26J called a general strike, but it largely failed.

However Batista’s offensive against the guerrillas in July 1958 failed and by the end of the year his forces had been driven back. On 1 January 1959 Batista fled and his army collapsed. The M26J took over, celebrated by a general strike lasting four days.

Castro’s political revolution was consolidated when leading Batista figures were tried and executed and the new regime passed a series of reforms, notably an Agrarian Reform Law in May 1959. Castro himself became prime minister in February 1959. In November 1959 pro-Castro and Communist (PSP) supporters took control of the trade union movement.

Towards the end of 1959, the US government began making plans to overthrow the Cuban government – and Castro began making links with the USSR. In May 1960 the government took complete control of the media. In the following months US oil and other businesses were expropriated. In April 1961 the US sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion failed and Castro declared the “socialist” character of the Cuban Revolution – in reality a social revolution that created the first Stalinist bureaucratic social formation in Latin America.

Why was there a revolution in Cuba 1959-61?

Lenin argued that revolutions come about when the ruling class is no longer able to rule in the old way, and the mass of people are no longer willing to be ruled in the old way.

This means trying to understand the circumstances that made a revolution possible – but also clearly identifying the agents involved, their aims and strategies for power.

Any explanation of the nature of the Cuban revolution has to grapple with five key issues:

1) The political economy of Cuba before and after 1959;

2) The nature of the Castro group that led the revolution, and other parties contending for power (e.g. the PSP);

3) The role of the US government in pushing Castro towards Stalinism;

4) The role of the USSR and the PSP in attracting the Cuban regime towards its orbit; and

5) The role of the working class and other classes in the process.

Most “left-wing” explanations of the Cuban revolution address these issues in the following way:

1) They emphasise the backward, dependent nature of Cuban capitalism, dominated by imperialism and ruled by a dictatorship often depicted as a puppet of the US.

2) They depict the Castro group as radical nationalists, but pragmatic revolutionaries who evolved their programme and strategy as they went along.

3) They emphasise the US government’s imperial bungling, which pushed the new regime away from bourgeois-democratic rule towards “socialism”.

4) The role of the USSR is presented as benign or even progressive, coming to the aid of the Cuban government when it came under attack from the US.

5) The working class is presented as an integral part of a popular, multi-class alliance that eventually put its representatives (the Castroites, sometimes with the PSP) in control.

In most “Trotskyist” accounts, this is sometimes dressed up as “permanent revolution”, whereby a process of growing over from a national-democratic revolution to a socialist revolution is asserted, with Castro’s leadership playing the locum role for a Marxist party. Differences about the nature of Stalinist rule in Cuba revolve around the extent of bureaucratic “deformation” or “health” of a “workers’ state”.

The central problem with this approach is that it displaces the working class from the centre of the analysis, substituting the Castro group as the progressive agency. The working class is at best perceived as a subordinate prop for the Castro regime – rather than the victim of its rule. Despite the absence of mass workers’ organisations, such as soviets (factory councils) or factory committees, and the absence of a Marxist party leading a class conscious working class to take power in its own interests, proponents of this view describe with ever great detachment from reality the manner in which the Cuban working class “rules” vicariously through the agency of Castro’s state. They forget that a “workers’ state” created without the active intervention of the working class is no workers’ state at all.

There are also right-wing explanations of Castro’s rise to power.

1) These emphasise the developed nature of Cuban capitalism in the 1950s and suggest that Batista would have given way to some form of bourgeois democracy.

2) They depict the Castro regime as Stalinist from the start, as a conspiracy that carefully concealed its true nature within a broadly democratic movement before foisting its real designs on the Cuban people after two years in power.

3) The US government is usually presented as moderate, protecting the interests of its businesses, sometimes making mistakes – but essentially benign;

4) By contrast, the USSR is portrayed as pulling Cuba towards its orbit from the beginning.

5) The working class is presented as duped by Castro’s promises – or is simply irrelevant to government-level machinations.

The main problem with this view is that it completely misunderstands the international context in which the Cuban revolution took place and the various contending forces that vied for power. It too fails to grasp the reality of the situation for Cuban workers before and after 1959, so provides no conception of what workers could have done in the situation – or what lessons can be learned for today.

Neither of these broad views offers a class analysis of the Cuban revolution. Neither grasps the dynamics of the period, the motives of the key social agents nor understands the trajectory the regime took between 1959 and 1961.

By contrast, Farber’s view is much more nuanced. To summarise it tersely:

1) The political economy of Cuban capitalism in the 1950s was defined by uneven development and Batista’s regime is understood as a Bonapartist formation, balancing between social classes with little social base.

2) Castro’s group was a declassed populist movement in the tradition of Latin American caudillismo, an active agent with its own aims and with internal tensions and pressures – and faced competitors for power. It created its own form of Bonapartist rule before choosing the Stalinist camp.

3) US policy emanated from its imperial role in the hemisphere and its priorities in the Cold War - consistent with its treatment of other regimes in Latin America.

4) The USSR pursued its own imperial state interests and was involved from the early days in the regime – acting as a pole of attraction and actively promoted as a model by the PSP.

5) The Cuban working class lacked the kind of independent politics necessary to fight for its own interests and self-rule. Workers were not the social force that made the revolution, nor its ultimate beneficiary – indeed the working class was hegemonised and effectively exploited by the new class that came to rule by 1961, under what Farber has called a “bureaucratic collectivist class society”. (1976 p.237)

To sum up, Farber’s book is exceptionally useful, dispelling the veil of romanticism that surrounds Castro’s Cuba on the left. It is vital contribution towards reorienting the left and a tremendous contribution towards understanding the nature of the Cuban regime today. With Fidel Castro’s death likely to set off a chain reaction inside and outside Cuba, Marxists have a substantial task in seeking to understand the Cuban social formation and its direction. This book helps us to do that work.Renegade Eye

Friday, June 16, 2006

A Muslim Barbie - please!

A journalist recently called to ask what I thought about the Muslim barbie doll, which is properly veiled and covered up in the Islamic tradition. Doesn't it offer the veiled child something she can relate to?

Please I said:

When a slave child has a slave doll to relate to;

When a child labourer has a doll which comes complete with a sweatshop;

When a girl who has been genitally mutilated has a doll with mutilated genitals;

and when a child 'bride' has a baby barbie doll dressed in white to relate to;

Then, I suppose, this veiled doll will also make sense...

That is, of course, if and when we have reverted back to the Middle Ages and full on barbarity.

The doll may help parents, the parasitic imams or Islamic states and groups impose the hejab on some girls but that does not change the undeniable fact that child veiling is nothing but child abuse.

******

To find out more on why I think child veiling is child abuse, Click Here.

To read Mansoor Hekmat's In Defence of the Prohibition of the Islamic Veil for Children,Click Here. It is a brilliant defence of the child. You can skip the first few paragraphs and get right into the crux of his argument.Maryam Namazie.

Please I said:

When a slave child has a slave doll to relate to;

When a child labourer has a doll which comes complete with a sweatshop;

When a girl who has been genitally mutilated has a doll with mutilated genitals;

and when a child 'bride' has a baby barbie doll dressed in white to relate to;

Then, I suppose, this veiled doll will also make sense...

That is, of course, if and when we have reverted back to the Middle Ages and full on barbarity.

The doll may help parents, the parasitic imams or Islamic states and groups impose the hejab on some girls but that does not change the undeniable fact that child veiling is nothing but child abuse.

******

To find out more on why I think child veiling is child abuse, Click Here.

To read Mansoor Hekmat's In Defence of the Prohibition of the Islamic Veil for Children,Click Here. It is a brilliant defence of the child. You can skip the first few paragraphs and get right into the crux of his argument.Maryam Namazie.

Monday, June 12, 2006

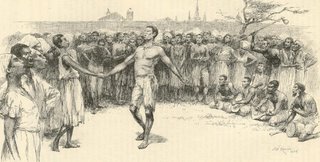

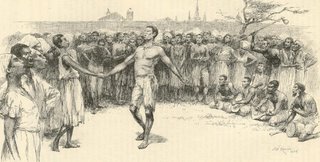

Congo Square New Orleans, LA

"All that New Orleans is - is a result of Congo Square" -- Tommye Myrick, Assistant Director of the Center for African and African American Studies at Southern University at New Orleans.

Congo Square 1810

In 1804 Fort St. Ferdinand was demolished, leaving an area of land, used for the commonwealth, called "Circus Place", and later called "Congo Square". Even before 1800, it was a place, where slaves gathered on Sundays. There was a law that stated, "slaves must be free to enjoy Sundays, or they were to be paid fifty cents a day if they worked." In 1817, the slaves were only allowed to gather for games, dances, weddings and funerals.

When they gathered, hollowed drums were used. They were hit with all body parts. Primitive banjos joined the instrumentation. The music, influenced by Creoles, was not monotone, and at times lovely and subtle.

The dance was creative. Sensual movements, without arms or legs, were particular to slaves owned by Latino masters.

Congo Square 1910

After slavery was abolished Afro-Americans, continued to meet there on Sundays. the music was varied. A new form was heard. This form was played on Sundays, and the sound reverberated all over the city. It was the birthplace of JAZZ.

Pre-Katrina Congo Park

Now Congo Square is part of Louis Armstrong Park in New Orleans. If an outdoor concert or political demonstration, in New Orleans, needs a gathering place, with a story to tell, there is Congo Square.

Congo Square survived Katrina.RENEGADE EYE

Congo Square 1810

In 1804 Fort St. Ferdinand was demolished, leaving an area of land, used for the commonwealth, called "Circus Place", and later called "Congo Square". Even before 1800, it was a place, where slaves gathered on Sundays. There was a law that stated, "slaves must be free to enjoy Sundays, or they were to be paid fifty cents a day if they worked." In 1817, the slaves were only allowed to gather for games, dances, weddings and funerals.

When they gathered, hollowed drums were used. They were hit with all body parts. Primitive banjos joined the instrumentation. The music, influenced by Creoles, was not monotone, and at times lovely and subtle.

The dance was creative. Sensual movements, without arms or legs, were particular to slaves owned by Latino masters.

Congo Square 1910

After slavery was abolished Afro-Americans, continued to meet there on Sundays. the music was varied. A new form was heard. This form was played on Sundays, and the sound reverberated all over the city. It was the birthplace of JAZZ.

Pre-Katrina Congo Park

Now Congo Square is part of Louis Armstrong Park in New Orleans. If an outdoor concert or political demonstration, in New Orleans, needs a gathering place, with a story to tell, there is Congo Square.

Congo Square survived Katrina.RENEGADE EYE

Saturday, June 10, 2006

Seven Palestinians picnicking on Beach Killed And Thirty Wounded By Israeli Artillery Attack

Hamas has called off its 16 month military truce with Israeli, after seven Palestinians were killed, and thirty were wounded, while picnicking at a beach in Gaza.

Israel has a history of inflicting collective punishment on Palestinians, causing widespread demoralization.

According to ABC.com, Kamal Ghobn said he had just arrived at the beach on a bus with about 50 relatives when the attack took place. "I was still parking the bus and everyone got out to go to the beach. As I locked the door I felt the thud of the shells and felt a sting in my side," said Ghobn, who was slightly wounded by shrapnel. Gobn said he saw four shells land.

The artillery fire scattered body parts, destroyed a tent and sent bloody sheets flying into the air. A panicked crowd quickly gathered, screaming and running around hysterically.

A sobbing girl lay in the sand, crying for her father. "Father! Father!" she screamed.

The body of a man lay motionless in the sand nearby.

Palestinian officials said seven people were killed and more than 30 wounded at the beach. Hardest hit was the Ghalia family, which lost six members, among them the father, one of his two wives, an infant boy and an 18-month-old girl.

On Thursday Israel conducted an aerial artillery attack killing Hamas leader Jamal Abu Samhadana. Thousands of Palestinians attended his funeral at a Gaza soccer stadium.

RENEGADE EYE

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Haditha is the result of your battlefield ethics

I can't stop thinking about the children executed by US forces in Haditha in November last year. What were they doing right before they were killed in cold blood? Where they playing or sitting on their doorsteps watching the world go by?

What must they have thought of the world they lived in? How scared they must have been when they saw the marines aim directly at them? How much pain did they feel? How long did it take for them to die? Did they die alone or in their mothers' arms?

And how did their mothers feel - helpless to save the lives of their precious little ones?

News of Haditha has driven me insane with rage. If you have still not felt it – numbed by the daily news of killings in Iraq - just try putting the faces of children you love, maybe your own or those of your siblings or close friends, in the places of those beloved who were murdered that day. Beloveds who will be missed; who will never be kissed or kiss again; who will never be tickled, or cuddled. Who are no more...

***

In response to this outrage, attempts at covering it up, along with reports of other such outrages, the US government has ordered troops to undergo a crash course in battlefield ethics.

Please; have some respect for our intelligence.

Haditha is the result of your battlefield ethics – one that similar to Islamic terrorism – indiscriminately targets civilians.

***

For those who think that US militarism is more palatable than Islamic terrorism, think Haditha...

Maryam Namazie

What must they have thought of the world they lived in? How scared they must have been when they saw the marines aim directly at them? How much pain did they feel? How long did it take for them to die? Did they die alone or in their mothers' arms?

And how did their mothers feel - helpless to save the lives of their precious little ones?

News of Haditha has driven me insane with rage. If you have still not felt it – numbed by the daily news of killings in Iraq - just try putting the faces of children you love, maybe your own or those of your siblings or close friends, in the places of those beloved who were murdered that day. Beloveds who will be missed; who will never be kissed or kiss again; who will never be tickled, or cuddled. Who are no more...

***

In response to this outrage, attempts at covering it up, along with reports of other such outrages, the US government has ordered troops to undergo a crash course in battlefield ethics.

Please; have some respect for our intelligence.

Haditha is the result of your battlefield ethics – one that similar to Islamic terrorism – indiscriminately targets civilians.

***

For those who think that US militarism is more palatable than Islamic terrorism, think Haditha...

Maryam Namazie